Table of Contents

Anu – God of the Heavens

Ancient Mesopotamian mythology recognized Anu as a significant deity. People held him in high regard as one of the chief gods in the Mesopotamian pantheon. Anu’s domain encompassed the heavens and the sky, and he occupied the role of the father of the gods. He played a pivotal role in shaping the cosmology and hierarchy of Mesopotamian deities.

Anu often appeared as a god who presided over the divine council, exercising his authority over various aspects of the universe and the divine order. His associations extended to matters of destiny and fate. Notably, Anu had several noteworthy descendants and divine offspring, such as Enlil and Enki, who also enjoyed prominence as gods in Mesopotamian mythology.

Anu’s importance and attributes exhibited some variations across different periods of Mesopotamian history and among different city-states, reflecting the evolution of the mythology and pantheon over time. Mesopotamia, the ancient region situated between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers (corresponding to modern-day Iraq and parts of neighboring territories), boasted a rich and intricate system of gods and goddesses, with Anu occupying a central role within this system.

Origin of Anu

The origins of the god Anu can be traced to ancient Mesopotamia, one of the earliest and most influential civilizations in the world. Mesopotamia, located in the region between the Tigris and Euphrates rivers, roughly corresponding to modern-day Iraq and neighboring regions, witnessed the integral presence of Anu within its pantheon. The worship of Anu dates back to the earliest epochs of Mesopotamian history.

Anu’s origins, like those of many ancient deities, are steeped in myth and legend. He often featured as one of the primeval deities, closely linked to the heavens and the celestial realm. The concept of a sky god or a deity associated with the heavens likely had deep roots in the early religious beliefs of the Mesopotamian people.

With the advancement of Mesopotamian civilization, the concept of Anu gained complexity and integration within the pantheon. He assumed the role of the father of the gods, with authority extending over diverse aspects of the divine order and cosmic hierarchy. Anu’s character and attributes evolved in tandem with the development of Mesopotamian mythology, adapting to the interpretations of the god by various city-states and cultures within the region.

The worship of Anu and his significance within the pantheon prominently featured in several Mesopotamian city-states, including Sumer, Akkad, and Assyria. While specific details about Anu’s origins may not be well-documented, the importance of his role as a deity in Mesopotamian mythology finds ample attestation in the historical and literary records of the region.

Family of Anu

In Mesopotamian mythology, Anu held a distinguished status as one of the supreme deities and the father of the gods. The intricate structure of the Mesopotamian pantheon hinged upon his family and divine lineage. Anu had several noteworthy divine descendants and family members, including:

Antu (Ki): Anu’s spouse and consort was Antu, also known as Ki. She often represented the earth, serving as a complementary and balancing force to Anu’s dominion over the heavens. Together, Anu and Antu constituted the divine couple, carrying profound symbolic meaning in Mesopotamian cosmology.

Enlil: One of the children of Anu and Antu was Enlil, sometimes referred to as the “Lord Wind.” He played a pivotal role in Mesopotamian mythology, associated with diverse aspects, including storms and air. Enlil occupied a potent position within the divine hierarchy.

Enki (Ea): Another offspring of Anu, Enki, functioned as a god of wisdom, magic, and water. He was renowned for his role in the creation of humanity and emerged as a prominent deity in Mesopotamian religion.

Ninhursag: Frequently known as Ninhursaga, this goddess was often regarded as the mother of humanity. In some Mesopotamian myths, she was even identified as Anu’s daughter, playing a part in the creation of human beings.

Inanna (Ishtar): The goddess of love, fertility, and war, Inanna, enjoyed a connection with Anu’s family. She was typically considered a granddaughter of Anu.

Nanna (Sin): Nanna, the god of the moon, featured as another member of Anu’s family. Often seen as the son of Enlil and Ninlil and the grandson of Anu, Nanna had his own significance.

The complex family relationships within the Mesopotamian pantheon exhibited variations among different city-states and time periods, contributing to diverse interpretations of the gods’ interconnections. Nonetheless, Anu’s role as the father of the gods and his familial associations constituted essential elements of Mesopotamian mythology and cosmology.

Epic of Gilgamesh

The Epic of Gilgamesh, a 3,200-year-old narrative that chronicles the protagonist’s exploits, remains one of the most renowned tales associated with the deity Anu. Archaeology made a sensational discovery of this ancient literary masterpiece, considered one of humanity’s earliest surviving works.

Gilgamesh, a king who was two-thirds divine and one-third human, became the ruler of the city of Uruk, being the son of Ninsuna and the grandson of Anu. Despite his godlike attributes, Gilgamesh was not a benevolent ruler; he encircled his city with walls and constructed magnificent temples using coerced labor. He also committed acts of sexual violence against women within his domain, leading his suffering subjects to beseech the gods for help. The divine response took the form of a man named Enkidu, who was sent to temper Gilgamesh’s excesses. Enkidu, a remarkable figure, and Gilgamesh forged a profound friendship, but Enkidu eventually perished due to a malady brought about by divine retribution. Grief-stricken, Gilgamesh embarked on a quest to the world’s farthest reaches in search of the secrets of the gods.

In the epic’s early segment, Enkidu lived among wild animals, sharing a water source with these creatures, which was discovered by a hunter who then informed his father of this remarkable wild man. They decided to send a prostitute to civilize him, believing that intimacy with a woman might quell his unconventional ways. After a week-long interlude with the prostitute, the animals shunned him, leaving Gilgamesh distraught. Seeking solace, he returned to the prostitute, who conveyed to him the pleasures of human life and the appeal of the city of Uruk.

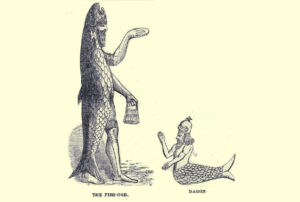

Upon learning of Gilgamesh’s excesses, Enkidu journeyed to confront the king. He prevented Gilgamesh from entering a bride’s chamber to commit violence, leading to a wrestling match between the two that concluded in friendship. They embarked on various adventures, including the slaying of a demon guarding cedar trees in a distant forest. Using the timber, they constructed a raft to return to Uruk. In the city, they encountered the love goddess Ishtar, who, spurned by Gilgamesh, entreated her father, Anu, to send the Bull of Heaven as retribution. This led to a seven-year famine, eventually resolved when Gilgamesh and Enkidu hunted and killed the bull. However, divine retribution followed, resulting in Enkidu’s agonizing death, leaving Gilgamesh devastated.

Determined to evade the fate that befell his friend, Gilgamesh embarked on a quest to find Utnapishtim, a figure akin to Noah in Mesopotamian lore. Utnapishtim, granted immortality by the gods after surviving a great flood, held the secret to eternal life that Gilgamesh sought.

After a series of adventures, Gilgamesh finally reached Utnapishtim, who recounted the myth of the great flood. Utnapishtim, warned by the god of wisdom, had built an ark to preserve all living creatures. The gods, later regretting their actions, vowed never to destroy humanity again. While men and women would still face mortality, the human species would endure.

Desiring immortality, Gilgamesh was put to the test. He was asked to stay awake for a week, but he failed promptly. Utnapishtim instructed him to don his royal garb and return to Uruk. As he left, Utnapishtim’s wife revealed a miraculous plant that could restore youth. Gilgamesh found the plant but lost it to a serpent that molted its old skin and rejuvenated. Gilgamesh, realizing he could not attain eternal life, embraced the idea that he would not live forever but that humanity would persist. Approaching the grand city he had built, he recognized his monumental achievement. Though he wouldn’t attain immortality, his legacy would live on, and his city would be his enduring testament.

Anu’s Historic Influence

In ancient Mesopotamian culture and religion, Anu, the god associated with the heavens, wielded substantial historical influence. Here are key aspects:

Religious Significance: Anu held a central role in the Mesopotamian pantheon, revered as one of the highest deities. Invoked in rituals and prayers, temples were dedicated to his worship.

Cosmological Symbolism: Anu’s association with the heavens shaped Mesopotamian cosmology, influencing perceptions of the divine and earthly realms.

Political Authority: Rulers claimed divine legitimacy through ties to Anu, believing divine support was crucial for state prosperity.

Cultural Influence: Anu featured prominently in Mesopotamian mythology and literature, notably in the epic of Gilgamesh.

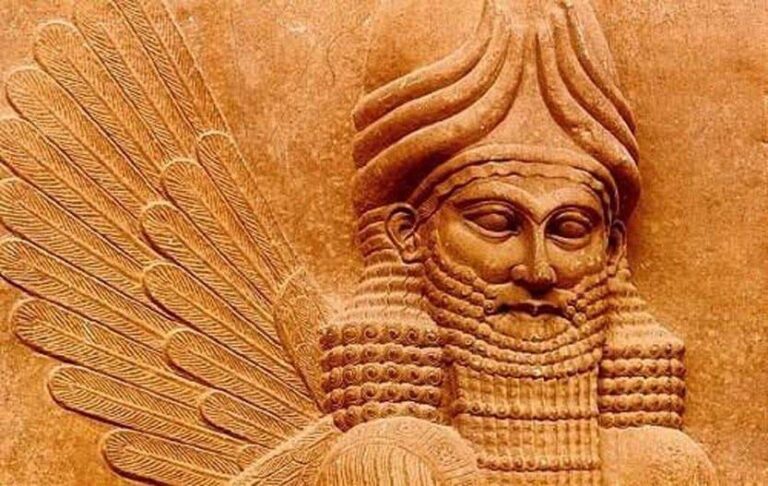

Art and Iconography: Depicted with a horned crown, Anu’s iconography symbolized divine authority, reinforcing his importance in visual culture.

References to Anu in historical inscriptions provide insights into religious and political aspects of ancient Mesopotamian society.

The influence of Anu and the Mesopotamian pantheon spanned a vast region, evolving over time with variations between city-states and periods. Regardless, Anu’s role as a celestial deity and father of the gods remained a significant and enduring aspect of ancient Mesopotamia’s history and culture.

Anu FAQ

Where is Anu?

Anu is associated with the celestial realm, representing the heavens and the sky in Mesopotamian mythology. He is considered a god of cosmic significance, presiding over the divine council.

Who is Anu in Gilgamesh?

In the Epic of Gilgamesh, Anu is portrayed as a significant deity and the father of the gods. The goddess Ishtar appeals to Anu to send the Bull of Heaven as retribution. Anu's role in the divine hierarchy influences the unfolding events in the epic, particularly in response to the actions of the hero Gilgamesh.